At 72, Manju Kothari nonetheless fondly remembers her mom’s recipe for gondh ke ladoo. Gondh, a pure edible gum, is combined with jaggery, flour and ghee to make this quintessentially Rajasthani winter candy. “I make them, too,” Manju shares, “I learnt it from my mom. However the style that she or my mother-in-law may carry out of those recipes, I can’t do the identical.”

Manju, a local of Churu, Rajasthan, now calls Surat, Gujarat dwelling. Regardless of her humble manner, her household recognises her as a culinary treasure trove. Her recipes, rooted in centuries-old traditions, are a testomony to her cultural heritage. Nevertheless, as time marches on, these age-old recipes danger fading into oblivion.

The altering dynamics of household buildings and the growing affect of recent meals tradition threaten to erode the wealthy tapestry of conventional Rajasthani delicacies. Native substances and time-honoured cooking methods are step by step disappearing, leaving a void within the culinary panorama.

Based by Dipali Khandelwal, a local of Jaipur, ‘The Kindness Meal’ seeks to protect and revive these forgotten dishes by specializing in generational sharing. Dipali’s personal journey with meals is deeply rooted in her childhood, rising up in a big, joint household the place meals was a central a part of their lives. “So far as I can keep in mind, I used to be very keen on cooking, very fond of making my very own recipes,” Dipali tells The Higher India.

“I grew up with an enormous household, so there was all this dialog, sharing and experimentation with meals,” she says. With a grandfather who was specific in regards to the high quality of each single dish he made, all the way down to the situation of the place the dates ought to come from, Dipali’s childhood was enormously knowledgeable by the meals tradition she noticed round herself.

Dipali spent numerous hours with Manju, listening to tales of the meals she grew up with in Rajasthan. Manju shared the various recipes she had realized from her elders, explaining how she continues to make them as we speak. These conversations gave Dipali invaluable insights into her subject of analysis, with Manju turning into considered one of her best inspirations in her journey to protect these forgotten dishes.

Why native dishes are disappearing in Rajasthan

For the previous seven years, Dipali has been working within the subject of artwork and cultural pageant curation throughout the nation. As this entails plenty of travelling and connecting with individuals on the grassroots, she ended up noticing a rising development.

Whereas city areas had been succumbing to the comfort of packaged and processed meals, rural communities had been witnessing the erosion of their culinary traditions. “I as soon as spoke to a girl who lived within the outskirts of Bikaner. She stated she doesn’t feed her son bajre ki roti (flatbread made out of pearl millets) as a result of he’ll ultimately transfer to town and if individuals see him consuming that as a substitute of a wheat chapati, they may make enjoyable of him,” she shares.

As Western influences more and more permeate native cultures, conventional meals habits are dealing with a decline. A way of cultural inferiority typically leads rural and tribal individuals to draw back from their conventional delicacies, making them reluctant to share or report their recipes.

Recalling an expertise working with a weaving cluster in Rajasthan, she says, “We used to have our meals at completely different properties every day. Nevertheless, one significantly scorching summer time day, I developed a headache and misplaced my urge for food. I declined the aloo chole puri that was ready for me and as a substitute requested the identical chaas and roti that her son was consuming.” Chaas roti or just buttermilk and chapati is commonly made throughout the summers when it will get too scorching to prepare dinner on an open hearth mud range. The dish is straightforward, made with leftover dried chapati bites crushed right into a bowl of chilly buttermilk with onions, mint, inexperienced chillies and salt. It’s a naturally cooling recipe that protects from the robust gusts of toilet.

“However she stated it in entrance of her son that it’s not one thing I would love as a result of it’s the meals of dehati’s (a derogatory time period for villagers). I believe that’s one incident, I can by no means take out of my head,” Dipali says.

“If any urban-looking individual asks them for native meals, they’ll find yourself making daal bati (Lentil and wheat bread balls), pondering that’s all we now have the style for,” she displays. The strain to adapt to city meals preferences and the commercialisation of native meals tradition was evident. However the irony, as Dipali discovered, was that these individuals had been sitting on a treasure trove of distinctive, domestically grown, and indigenous meals — meals that had been on the verge of being misplaced endlessly.

Initially, Dipali’s journey started as a private quest to grasp her roots. This led her to embark on in-depth analysis, exploring the distant corners of Rajasthan. She meticulously documented native consuming habits, indigenous substances, their seasonal availability, storage methods, and the various recipes they impressed.

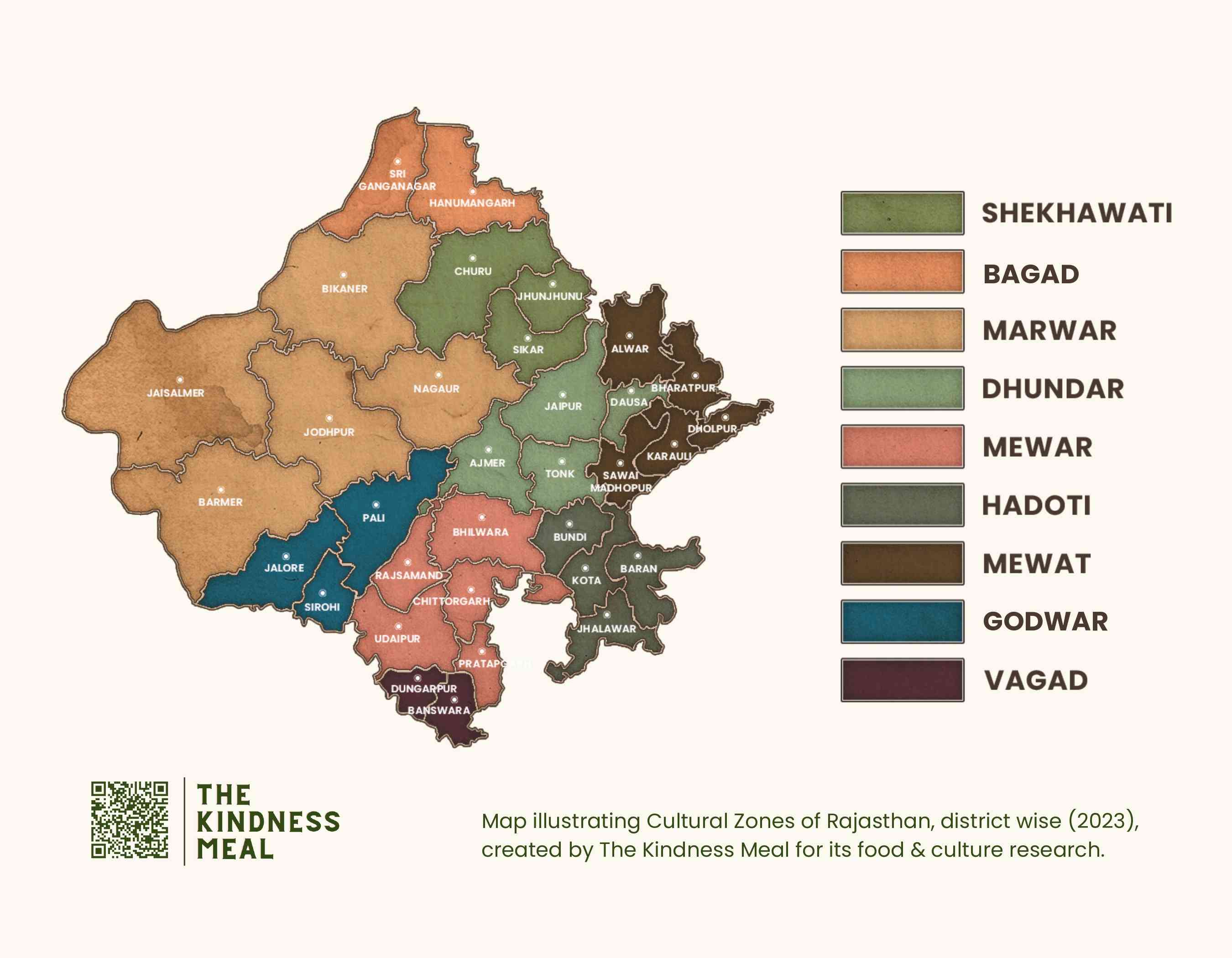

She broadly identifies 9 cultural zones in Rajasthan on the idea of geography, the agricultural options, and language. Resulting from its location, Marwar, or the desert area of Rajasthan, has all the time trusted solid substances as a substitute of greens. Elements like pholga or fogla (Cooling meals), ber (Rajasthani Plum), ker shangri (Caper berry) are generally consumed. A lot of the Rajasthani meals served across the nation like laal maas (Crimson Meat Curry), daal bati, ker shangri ki sabzi (Caper berry curry) all come from these areas. However what about the remainder of it?

For instance, the Bagad area which contains Hunumangarh and Ganganagar, is also called the Punjab of Rajasthan, due to its lush and fertile lands. Their consuming habits are very completely different from Marwar. The Chambal river flows within the Mewar area, and due to the supply of contemporary water, they’ve plenty of dishes that embody fish. However as a result of it doesn’t match into the homogenous thought of Rajasthan, all that is typically excluded.

By way of her curated eating experiences and pop-up occasions, Dipali brings out these underrated elements of Rajasthani delicacies. She introduces these dishes to a wider viewers and helps them develop a deeper connection to the meals they’re having fun with by giving them a radical understanding of its origins and cultural significance.

Encouraging kids to doc their household recipes

One of many core ideas of ‘The Kindness Meal’ is generational sharing, the place older generations cross down their data of meals and recipes to youthful individuals. That is essential in a time when conventional recipes are being misplaced because of the altering dynamics of household buildings and life.

They organise ‘Meals Tradition Play Dates’ for kids aged between seven and 14, which goals to show kids in regards to the significance of meals of their cultural heritage. “We prepare the children to be ethnographic and doc their household recipes,” Dipali explains. “It additionally creates this sense of marvel — what was the meals, and the place is it coming from? And makes you need to know extra.” The kids are inspired to talk to their members of the family in regards to the meals they ate rising up and the tales round it.

Dipali remembers a heartwarming story from considered one of their classes, the place a baby shared her father’s household’s custom of consuming “jadi ber ki chai”, a tea created from the dried fruit of the ber tree, to assist her grandmother with insomnia. The kid’s father was extremely moved by the reminiscence, as he realised how necessary this household ritual had been, and the way it had slipped away when the household moved to Jaipur.

Sanjana Sarkar, 38, who works with the French Embassy and serves because the director of Alliance Française, Jaipur, describes herself as somebody who “lives to eat”. Throughout one of many Meals Tradition Play Dates, kids from varied colleges, various by way of monetary backgrounds, got here collectively. “On the primary day, we seen that when requested about what kind of meals they like, all of them had a typical desire for processed and packaged meals,” she remembers; “However the subsequent day, once they got here with their tales about ber ki chai (Rajasthani plum tea) and lehsun ki kheer (Garlic rice pudding), the curiosity was palpable.”

On the finish of the 2 day workshop, they made a binder with all the standard recipes shared by the kids. “The binder is stored in our library right here, and we’ve archived these recipes to do our half in preserving this wealthy meals heritage,” she says.

“We need to encourage kids to get pleasure from their very own dwelling, neighborhood, or state’s meals and champion it earlier than all of it begins to look and style the identical.” By documenting and sharing these recipes, ‘The Kindness Meal’ helps future generations not lose contact with their culinary heritage.

Serving to individuals hook up with their roots

Manohar Kabeer (32), a communications skilled, discovered about ‘The Kindness Meal’ when a buddy shared a reel of theirs. “I felt as if I used to be the beneficiary of what she was attempting to do,” he shares. A Rajasthani who grew up in Maharashtra, Manohar was taken again to summers in his nani’s (grandmother) home. “There could be plenty of dishes made with bajra (pearl millets), I particularly keep in mind the rabdi (a thickened, sweetened milk dish). Then there have been foraged meals like mangodi (a variation of the mung bean), and sangri (desert bean) that may be used to make sabzi,” he says.

Manohar’s dad and mom moved to Maharashtra within the Nineties, however his journeys again had been marked by the meals they ate. His nana (grandfather) owned buffaloes and camels. “I even keep in mind waking as much as the sound of the bilona (a wood churner which was used to churn curd into fermented makkhan or butter). We had been very grasping about it, so we’d eat as a lot as attainable in these two months,” he fondly remembers. After shifting out and residing alone, he began ordering Rajasthani meals on-line, and infrequently selected gatte ki sabzi (Gram flour dumpling curry), though he admits that his mom doesn’t think about it “correct meals”.

“Each state in our nation is definitely a rustic in itself. So, you can’t label it as simply Rajasthani meals or Gujarati meals. Each neighborhood, tradition, geography, modifications each few kilometres and we have to begin talking about these micro cuisines earlier than later,” Dipali says.

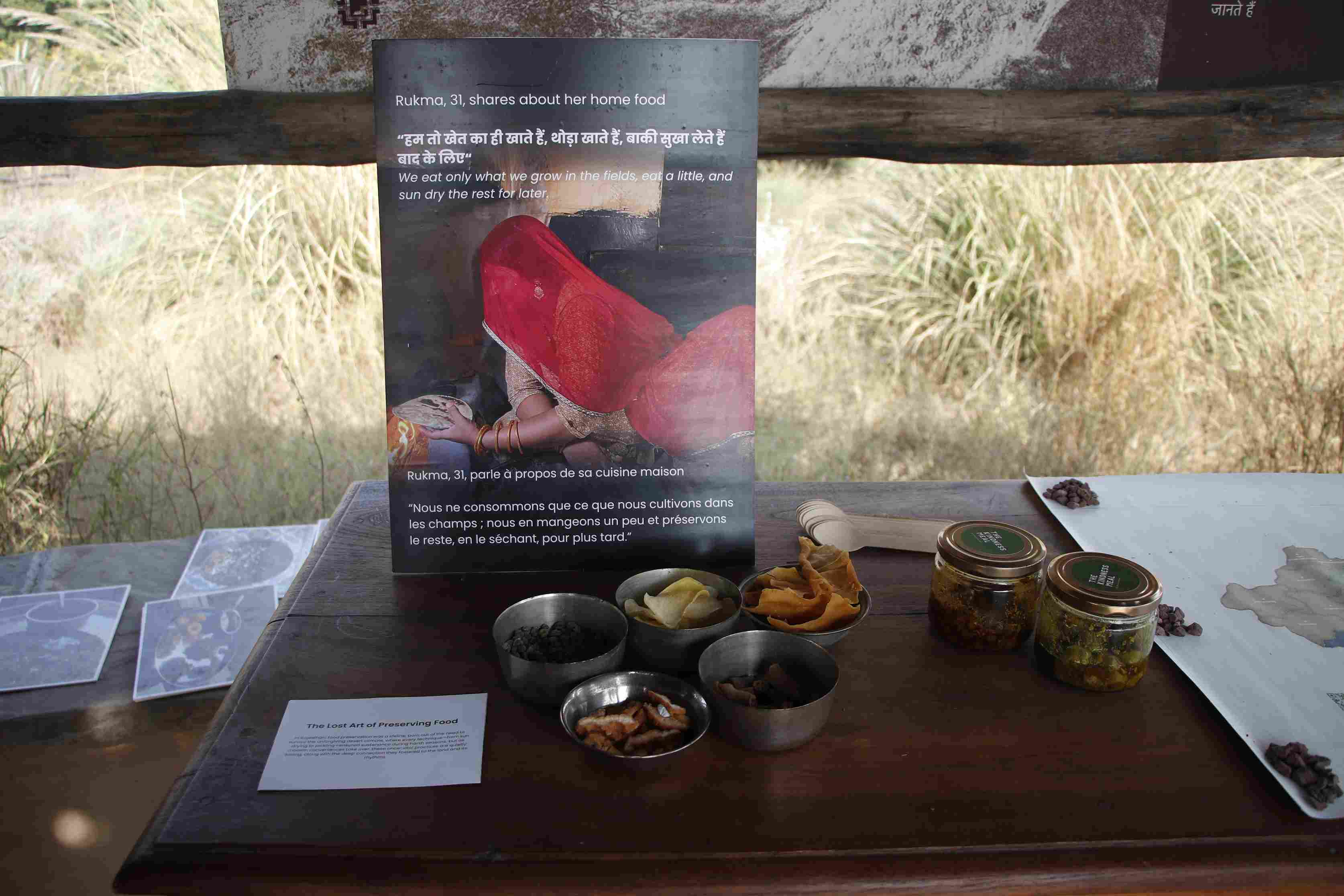

Other than analysis and documentation, and bringing eyes to Rajasthani meals by way of her informative Instagram movies, Dipali additionally curates pop-up touring museums, that are stuffed with tangible issues from throughout Rajasthan. There are substances and meals that persons are free to style together with different elements equivalent to picture essays, audio tales, artworks. “Even Rajasthani individuals come and inform us that they’ve heard about these substances nevertheless it’s the primary time seeing them,” she shares.

“The entire creation is manufactured from a number of elements, preserving in thoughts that if I’m taking it to, let’s say, Meghalaya, it ought to make the viewer suppose not nearly my tradition but additionally of their very own. I would like this to be a contact level the place anyone interacts with it, they return dwelling and name their mom, asking about an ingredient or for a recipe. One thing they used to have as a baby they usually don’t make it anymore,” she says.

As Dipali says, “Meals isn’t just a matter of leisure or sustenance. It’s additionally an identification.” And thru her work, she is guaranteeing that the wealthy culinary traditions of Rajasthan — and past — are preserved for generations to come back.

Edited by Arunava Banerjee, All pictures courtesy Dipali Khandelwal